Listen to Episode 76 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or anywhere podcasts can be found!

The evolution of horses is not only one of the classic evolutionary stories of the ancient past, it’s also an incredible story of scientific discovery and adjustment. From the dawn of the Age of Mammals to the domestication of modern work animals, we’re taking a trip through Horse Evolution.

In the news

Different dinosaurs replaced teeth at different rates

Alligator tool use? New study raises some doubts

Microscopic fossils reveal the early evolution of animal embryos

A Styracosaurus named Hannah with an asymmetrical head

Horses

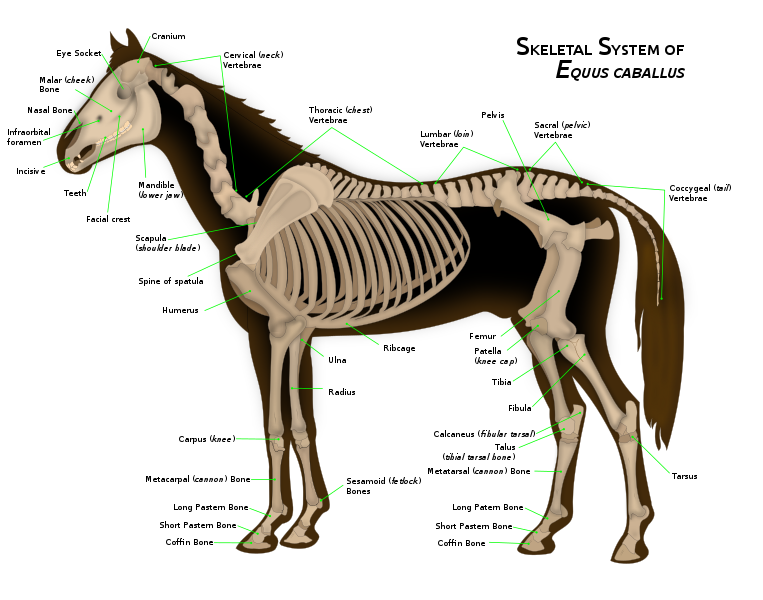

Horses belong to a group of mammals known as the ungulates, which include all hoofed mammals and their close relatives. This group is split into the artiodactyls (even-toed ungulates), and perissodactyls (odd-toed ungulates).

Today, there are about 10 species of horses, zebras, donkeys, and wild asses. The most abundant equines in our world are domesticated horses, which include over 400 different breeds. In fact, Przewalski’s horse, which lives in Asia, is thought to be the only living horse species that is truly wild, having never been domesticated. Zebras, too, have avoided domestication. All other wild horses are feral populations of domesticated horses

The history of horse domestication is complex, and there are many unanswered questions. Archaeological evidence indicates that the domestication of horses goes back at least 6,000 years ago in Central Asia, but it’s debated whether horses were domesticated once or multiple times.

Horse Evolution

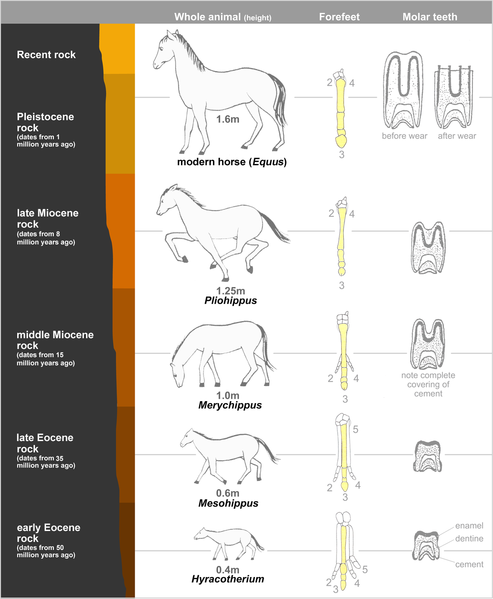

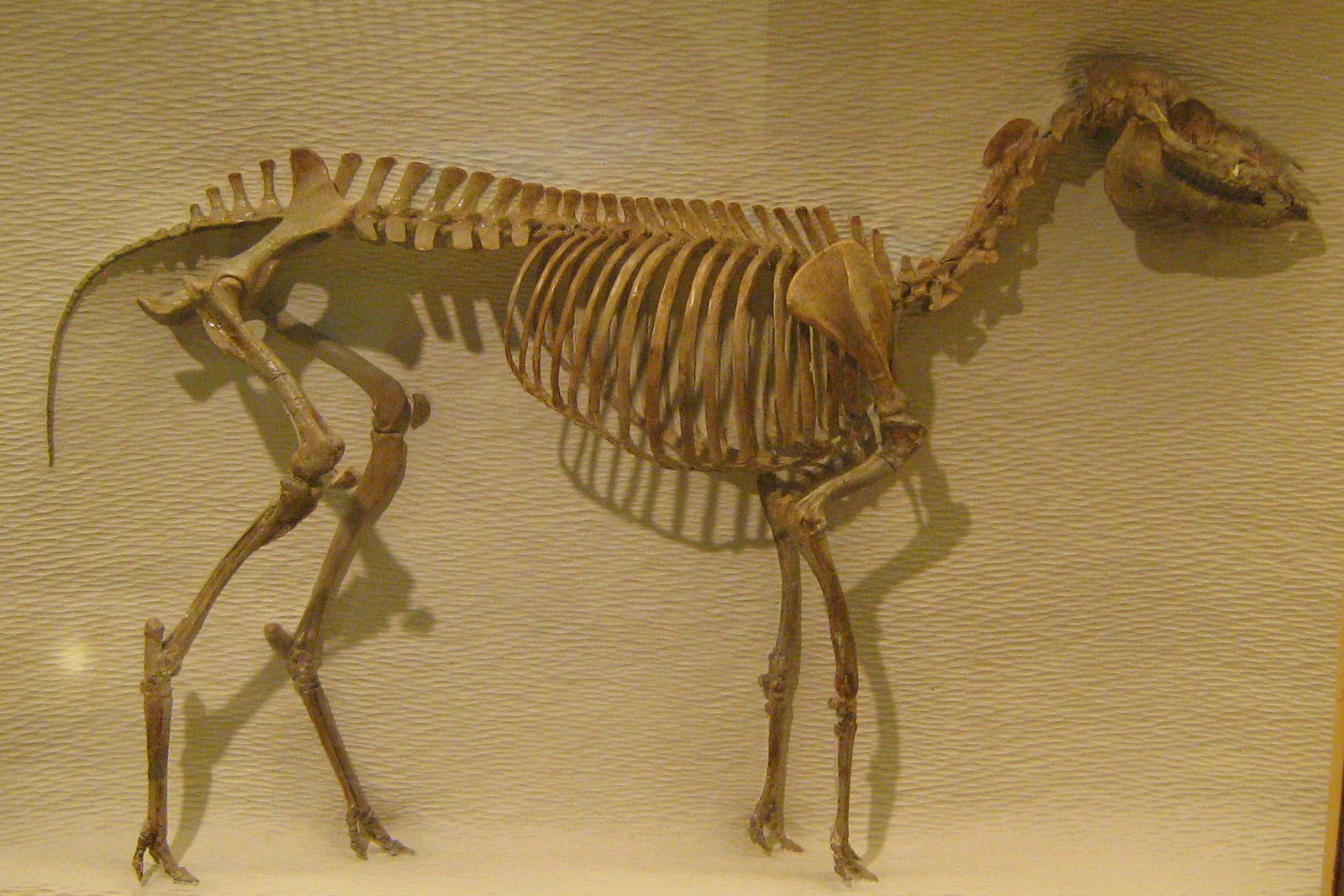

Few evolutionary stories are as iconic as that of horses. For a long time, horse evolution was championed as a clear example of the gradual, linear change that Charles Darwin had predicted would appear in the fossil record. It’s been known since the 1800s that early horses were small browsing animals with multiple toes on each foot (as opposed to modern horses’ single toe), and it seemed that over time horses grew in size, took up grazing, and lost all but the middle toe.

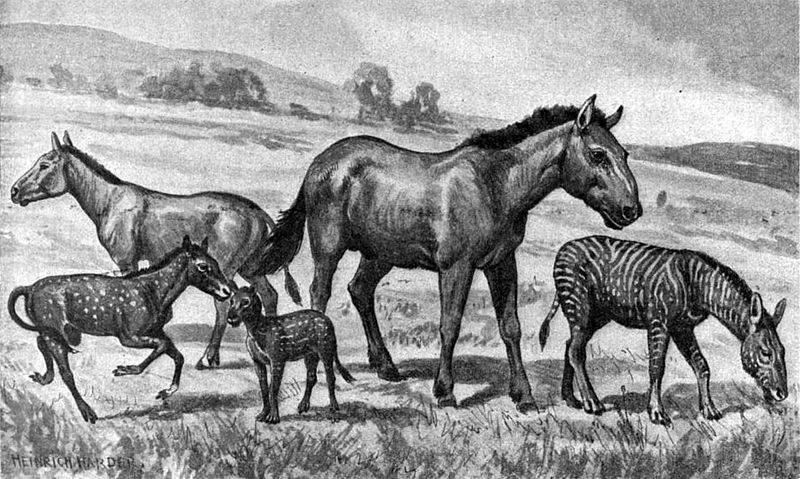

Those changes did indeed happen, but it was not nearly so simple as a linear progression. Over millions of years, horses and their ancestors came in many shapes and sizes. Some grew larger and more similar to modern horses, while others remained small, many stuck to browsing in forests, and many even retained their multiple toes.

The earliest ancestors of modern horses lived during the early Eocene Epoch, around 55 million years ago, and for many millions of years, horse ancestors were relatively small browsers. But during the Oligocene Epoch, when global climate began to grow cooler and drier, and grasslands spread across the globe, horses began to take on more familiar shapes.

Starting around 30 million years ago, we see some horse ancestors developing teeth more adapted for grazing, as well as early examples of toe reduction.

Horse diversity reached its peak around 20 million years ago, during the Miocene Epoch. As grasslands continue to spread, we see some horses growing larger body sizes and more grazing-adapted teeth, and some reducing all but the central toe of each foot. At the same time, other horses remained small, many-toed forest dwellers.

During the Pliocene Epoch, starting around 5 million years ago, as the Earth continues its cooling and drying trend, the first true members of Equus appear, large-bodied and functionally single-toed. These quickly become the dominant group of horses on the planet while the three-toed horses, so common in the Miocene, dwindle until they disappear completely around one million years ago.

Most of horse evolution takes place in North America, which is also where we get most of our knowledge of the horse fossil record. But at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, about 12,000-8,000 years ago, horses go extinct in the Americas, along with many other large mammals.

It wasn’t until the 1600s that horses reappeared in their ancestral homeland of North America, reintroduced by Spanish conquistadors.

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!

Can you please make an episode on t-rex?

LikeLiked by 1 person

We sure can! Added to the list!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe that some recent research has found that there are *no* Equus caballus that have purely wild ancestry; Przewalski’s horse has been found to have descended from feral stock. This is both interesting and sad.

The plasticity of horse breeds is amazing; the smallest non-dwarf miniature horses are under 96.5 cm at the shoulder, while the largest are the Shire, which can be over 2 m at the shoulder, without the health problems that plague dogs at the extreme sizes. The evolutionary question buried in that observation is “Why?” How can horses (and dogs) have such a vast range of sizes within a species, which seems to be (I don’t think other species have been bred so intensely for sizes) rare for, at least, mammals?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Staying in the world of mammals (I like mammals; some of my best friends are mammals), an episode on camelids.

——————–

Relevant to this episode, I’ve seen an article (not in a refereed journal, alas) that Przewalski’s horse is not a remnant wild horse population, but is descended from captive stock. Is this true or am I misunderstanding something?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good idea, Ed! Added to the list.

Also, yes, there was a recent study that found evidence to suggest Przewalski’s horse might not be wild after all. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/02/ancient-dna-upends-horse-family-tree

LikeLiked by 1 person