Listen to Episode 96 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or just search for it in your podcast app!

Kangaroos, koalas, opossums, possums, Tasmanian devils, and their relatives … they all have a few things in common: an unusual reproductive strategy, a pouch for their young, and a shared evolutionary history that separates them from the majority of living mammals. This episode is all about Marsupials.

In the news

Evidence of air-breathing in a new species of eurypterid sea scorpion

Unexpected skull bones in a placoderm, new perspective on fish evolution

DNA reveals how mastodons migrated in response to climate change

New dinosaur species discovered in a collapsed burrow

Meet the Marsupials

Our modern world is home to three major groups of mammals: monotremes, marsupials, and placentals. Monotremes include echidnas and platypuses; placentals include nearly all mammals alive today (that means you); but marsupials are the focus of this episode.

Top left: common wombat (image: JJ Harrison / CC BY-SA 3.0);

Top center: woolly opossum (image: Charles J Sharp / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Top right: Virginia opossum with young (image: Specialjake / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Bottom left: Tasmanian devil (image: Mike Lehmann / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Bottom center: red kangaroo (image: Rileypie / Public domain)

Bottom right: sugar glider (image: Dawson / CC BY-SA 2.5)

The three groups are distinguished in part by their reproductive habits. Monotremes lay eggs, and placentals give live birth to young that are nourished during development by a placenta. Marsupial reproduction is comparatively strange – from our perspective at least! Marsupial embryos develop inside the mother with the help of a short-lived type of placenta, but early in development, the young (a.k.a. a joey) is “born,” leaving the womb to crawl along mom’s body to a pouch (a.k.a. a marsupium) where it spends the rest of its development with its mouth affixed to a teat for nourishment.

In terms of skeletons, marsupials have a number of features in their skull, limbs, and elsewhere that distinguish them from other mammals. Most notably, they have lots of teeth! In terms of dental formula, placental mammals tend to max out at around 42 total teeth, while marsupials can have up to 50!

Image: Dawson/ CC BY-SA 2.5

Today, marsupials are found almost entirely in Australia and South America, with one lone species, the Virginia opossum, in North America. Over 300 living species include forms that are strongly convergent with placentals – such as very rabbit-like bilbies, sugar gliders who soar like gliding rodents, and the so-called marsupial moles – as well as more unique cases like kangaroos and wallabies.

A brief history of marsupials

Marsupials belong to a broader group called Metatheria. Genetic evidence suggests metatherians originated in the Jurassic Period, somewhere around 160 million years ago, but the oldest fossils of the group belong to Sinodelphis from China, around 100 million years ago. Early metatherians spread across Asia, Europe, and North America before one branch eventually gave rise to true marsupials.

The oldest known marsupials are a group called Peradectes, which lived in North America around 65 million years ago. It’s also around this time that marsupials and their fellow metatherians make the move down to South America just before it fully disconnected from the northern continents.

South American metatherians soon diversified into a variety of groups, including early cousins of the opossums that still live on the continent today. Alongside them were the near-marsupial sparassodonts, a group of carnivores that included the hyena-like borhyaenids, the weasel-like Cladosictis, and the saber-toothed Thylacosmilus (which was maybe not-so-saber-toothed).

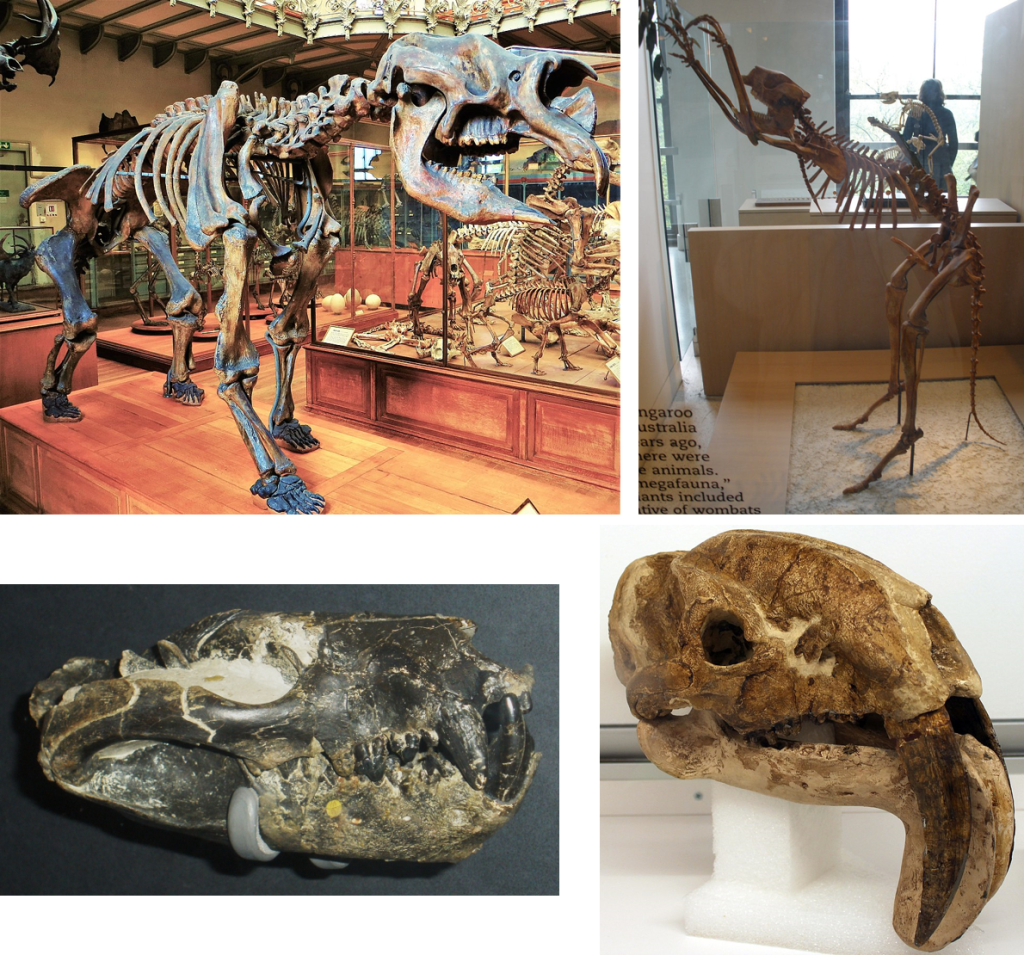

Marsupials also made their way across the southern continents, and by 55 million years ago, at least one group had spread far enough across Antarctica to reach Australia. These early arrivals seem to be responsible for the ultimate evolution of modern Australian marsupials, as well as some impressive extinct examples like short-faced kangaroos, marsupial “lions,” and rhino-sized “giant wombats” called Diprotodon – the largest marsupials in history. Many of these super-sized marsupials went extinct at the end of the Ice Age.

Top left: Diprotodon, a “giant wombat” (image: Ghedoghedo / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Top right: Simosthenurus, a short-faced kangaroo (image: Ghedoghedo / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Bottom left: skull of Borhyaena (image: Ghedoghedo / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Bottom right: skull of Thylacosmilus (image: Jonathan Chen / CC BY-SA 4.0)

About 3 million years ago, South America reconnected with North America, permitting an exchange of species called the Great American Biotic Interchange. Among the animals that moved north were the ancestors of North America’s single living marsupial species, Virginia opossums, which are thought to have made the trip within the last million years.

More questions

Why Are There So Many Marsupials In Australia?

Marsupial Evolution: A Limited Story? (semi-technical)

Why Are There Fewer Marsupials Than Placentals? (technical)

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

- Episode 50 – Australia

- Episode 32 – Naracoorte Caves, Australia

- Episode 74 – South America

- Episode 43 – The Great American Biotic Interchange (GABI)

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!

I have a plants request: gymnosperms, but especially the gymnosperms of the Mesozoic.

LikeLike

Onto the list!

LikeLike