Listen to Episode 99 on PodBean, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite alternative!

They’ve been on Earth for around 400 million years, they have occupied nearly every ecosystem on land for most of that time, they come in a more dazzling diversity than arguably any other group of life, and they have a fascinating, complex, and deep evolutionary story. This episode, we try our best to touch lightly upon the Evolution of Insects.

In the news

Strange pointed beak belongs to a new species of pterosaur.

Jaw fragment reveals long history of giant false-toothed birds in Antarctica.

These gliding dinosaurs might not have been all that great in the air.

First-ever glimpse at a fossilized dinosaur cloaca.

Insects

It’s difficult to describe just how incredibly diverse insects are. Estimates for their abundance vary, but according to recent data (in this case, Stork 2018), over one million living insect species have been described scientifically, and some estimates suggest there may be millions more left to discover.

Images by a variety of authors (see here) / CC BY-SA 3.0

Insects are found on just about every landmass on Earth, in just about every habitat, and they occupy just about every niche you can think of. Among their ranks are some of the most significant herbivores, detritivores, and parasites in the world. Some major insect groups, like termites and cockroaches, comprise merely thousands of known species, while others exceed 100,000. And of course, there are beetles, with nearly 400,000 identified species and more to come.

Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung / CC BY-SA 2.0

Image by Al2 edited by Muhammad Mahdi Karim, CC BY 3.0

Now, you may think that an insect, being small and often delicate, would be unlikely to be fossilized and discovered by paleontologists, and you would be right. But if you think that makes them rare in the fossil record, think again; their sheer numbers outweigh preservation bias. Insect fossils are found all over the world, as fragmentary remains, 2D impression, 3D replacements, trace fossils, and of course famously in amber.

This record reveals that insects have been abundant in land ecosystems for about as long as there have been land ecosystems, going back some 400 million years. Earth is now, and has been for a long time, a planet of insects.

Insect Evolution

The oldest fossil insects come from the Devonian Period, and they’re quite rare. Early examples like Rhyniognatha from Scotland and Strudiella from Belgium look a bit like modern-day silverfish, which might be a good image of what the earliest insects were like. These oldest insects were some of the very first animals to live on land, alongside other athropods like early arachnids and myriapods.

Right: rock bristletail by Bruce Marlin / CC BY-SA 3.0

These are among the basal-most members of the insect family tree, and are similar to the oldest insect fossils. The earliest insects might have looked somewhat like these.

It’s always difficult to say for sure what drives the success of any particular group of organisms. Insects have a lot going for them: they reproduce quickly and in large numbers; their anatomy is highly variable and adaptable; and they seem to consistently do well during mass extinction events. But if any one feature could be said to be their winning adaptation, it’s got to be flight.

Insects probably evolved flight a single time back in the Devonian Period. Unfortunately, like most cases in the evolution of flight, there are few clues in the fossil record as to exactly how or when this happened. Debates continue to this day as to whether insect wings evolved from paranotal lobes on the sides of their bodies or from the same body parts as gills and legs, with recent research still providing clues.

Later evolutionary innovations allow other groups of insects to fold their wings over their bodies and adapt them for camouflage, protection, communication, and more. For over 100 million years, insects were the only creatures that could fly, and most living species still do.

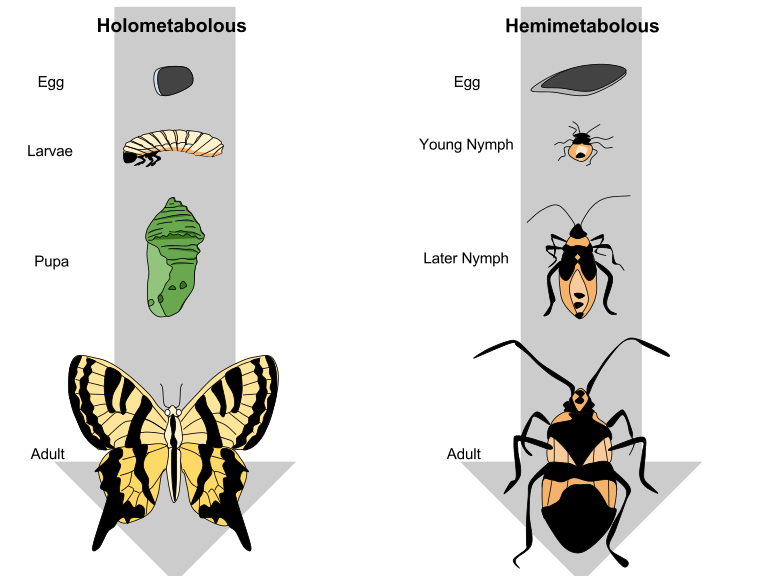

Another major innovation early in insect evolution was that of complete metamorphosis. Early insects likely didn’t metamorphose at all (ametaboly), like living silverfish; the first flying insects probably had incomplete metamorphosis (hemimetaboly), going from nymph to adult via a series of molts like living dragonflies and mayflies; but sometime during the Carboniferous, at least one group developed complete metamorphosis (holometaboly), including a larval, pupal, and adult stage. Exactly how this transition occurred is also still a subject of investigation.

Image by Username1927 / CC BY-SA 4.0

A major theme in insect evolution has been co-evolution, a process where different groups of life have major impacts on each other’s evolution. The classic example is the link between insects and flowering plants. Many modern groups of insects diversify around the time of the evolution of flowering plants, and to this day insects are major pollinators and herbivores of flowering plants, with many examples of the two groups evolving specifically to co-exist.

There are also great examples of mammal-insect co-evolution, such as the several independent origins of specialized ant-eaters (including numbats, aardvarks, pangolins, and of course, anteaters) as well as the close co-speciation between lice and their hosts.

So Much More

Most of our info in this episode came from the book Evolution of the Insects by Grimaldi and Engel.

—

If you enjoyed this topic and want more like it, check out these related episodes:

We also invite you to follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, buy merch at our Zazzle store, join our Discord server, or consider supporting us with a one-time PayPal donation or on Patreon to get bonus recordings and other goodies!

Please feel free to contact us with comments, questions, or topic suggestions, and to rate and review us on iTunes!